Independent feeding is considered one of the most significant milestones hospitalized infants should master before being discharged.1

While some preterm infants will progress to full oral feedings prior to NICU discharge,2 many continue to have feeding challenges at term equivalent age3 and beyond.4 One reason for this is that preterm infants are more likely to experience oromotor difficulties that negatively affect their ability to independently feed.1

Delay or failure to transition from tube feeding to independent oral feeding can lead to both short- and long-term consequences.5

Understanding the development of oral feeding skills is critical to drive appropriate care practices for oral feeding assessments and treatments to improve the outcomes for this fragile infant population.

Development of oral feeding skills

The earliest movements seen for oral feeding skill development are suck and swallow, which emerge in the fetus around 12-13 weeks gestational age.6 These skills start sporadically but gradually grow in strength, rhythmicity, coordination and timing by term gestation, allowing the infant to feed successfully at birth. The intra-uterine environment provides the growing fetus with appropriate oral motor experiences to practice and refine these skills. For example, near-term fetuses are seen on ultrasound sucking and swallowing approximately 210-760 mL of amniotic fluid a day in preparation for swallowing milk after birth.7

At birth, full-term infants will present with the necessary physiologic stability and neurodevelopment to feed independently from a breast or bottle. The operational definition of oral feeding skills is the infant’s ability to coordinate sucking, swallowing and breathing; regulation of oral‑motor function; regulation of sensory function; ability to maintain psychological stability; and regulation of feeding behavior to caregivers or the environment to fulfill nutrition needs.8 For an infant to achieve independent oral feedings, they must do all this while maintaining stable nutritional intake for growth and development.

An important precursor to an infant’s ability to orally feed is an organized and strong non‑nutritive suck (NNS) — a reflex that, in full‑term infants, follows a predictable and rhythmic pattern as a response to tactile input in or around the mouth.3 NNS is a foundational skill that involves the coordination of compression bursts of sucking and pause intervals for breathing, in the absence of liquids. Each burst contains 6-12 suck cycles, at a rate of two sucks per second.9 The maturation and coordination of the NNS serve as a foundational skill that precedes nutritive sucking skills.

Nutritive suck involves nutrients, such as milk, being obtained from a bottle or breast by way of the infant alternating suction and compression on the nipple. Nutritive suck is a highly complex task requiring the coordination of suck, swallow and breathe with a 1:1:1 ratio, at a rate of one per second; infants are seen to coordinate 10-30 suck-swallow-breathe bursts before pausing for a respiratory break.10 Precise timing, coordination and muscular strength are required to express milk into the oral cavity, propel it posteriorly to the pharynx, protect the airway, clear the bolus into the esophagus and manage residue safely, all within one second.

This is why NNS precedes nutritive suck — it allows the infant to practice the oral movements and obtain appropriate coordination of suck and breathe, before needing to also control for liquid swallowing. While full-term infants develop these skills in a typical and predictable way, infants born preterm experience a vastly different learning environment, and therefore present with a different developmental pathway to learn how to orally eat.

An important precursor to an infant’s ability to orally feed is a well‑organized and strong non‑nutritive suck

Effects of prematurity

When an infant is born preterm, they do not receive the same length of time to grow in the womb or receive similar positive experiences to refine their oral motor skills, as compared to a full-term infant. Immediately after birth, they are admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) where they are exposed to many life-saving interventions — some of which may inhibit normal neurodevelopmental experiences.

In general, their development may be disrupted by comorbidities such as respiratory disease, brain injury and gastrointestinal disease, which limit opportunities to learn NNS and expose them to oral-sensory experiences.11-13 Preterm infants with respiratory disease require respiratory devices which limit important sensory and motor experiences during a critical period of brain development and lead to more disorganized sucking and dysfunctional oral feeding. Specifically, prolonged endotracheal intubation, positive pressure ventilation devices taped to their faces and suctioning of secretions have been found to result in oral aversions and oral feeding difficulties.2,13,14-16

Other factors, such as poor physiologic stability in the autonomic, motoric and state subsystems may limit these infants from achieving and maintaining adequate stability for successful oral feedings. Preterm infants may demonstrate poor oxygenation, increased energy expenditure and the presence of fatigue during oral feedings.17 Their ability to express pre-feeding behaviors such as feeding readiness cues may further limit their opportunities to learn the complex skill of feeding by mouth.18-24

Neural immaturity is another significant factor that affects preterm infants’ oral feeding development. It is important to note that due to innovative medical advances, NICUs can now save infants born at 22 weeks gestational age;25 however, the neural pathways necessary for safe oral feedings do not emerge until approximately 32-34 weeks corrected gestational age.26-28 Infants born before this age require alternative methods for primary nutrition, such as total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and enteral nutrition via orogastric (OG) or nasogastric (NG) feeding tubes until they begin oral feedings. Providing these infants with appropriate sensory experiences to mimic the stimulation they would have received in the womb, specifically NNS, is critical to their feeding development.

Key effects of prematurity

- Neural immaturity2

- Poor physiologic stability17

- Increased energy expenditure17

- Respiratory, neurologic and/or gastrointestinal comorbidities11-13

NNS development in the preterm infant

Preterm infants’ ability to suck has a substantial impact on their health, state control and developmental outcomes. Similar to full-term infants, NNS is an important precursor for a preterm infant’s ability to orally feed,29-30 however, these infants consistently present with immature sucking for numerous reasons. First, gestational age was found to be a direct predictor of sucking skill and feeding maturation.31 The lower the gestational ages, the less mature their skill levels. Second, physiologic stability and neurodevelopmental status are intricately linked to sucking skills.

Silberstein et al revealed that preterm infants who had poor reactivity to stimulation, poor motor responses and poor state control were found to have slower suck rates.32 One suck measure, called the spatiotemporal index (STI) represents how consistently an infant can organize their NNS skills. A relatively high STI value (80-90) indicates inadequate coordination of suck cycles during NNS bursts and is typical of premature infants at 28-35 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA), whereas a low STI value (20-40) indicates a well-formed burst motor pattern with low variation across burst events as seen in full-term infants.30 Higher STI scores suggest immature neurologic status33 but was found to decrease with PMA as the infant continues to refine the skill.34

Other NNS measures such as suck strength, number of sucking bursts per minute and number of sucks per burst have also been found to be reduced in preterm infants.29 Similar to the STI, as PMA increases so do sucking skills, which is also associated with an increase in oral feeding abilities.30 Unfortunately, they do not mature enough to equal what a full-term infant would achieve. The result is that premature infants continue to have feeding difficulties throughout their NICU stay, at discharge and at home well into their childhoods.4

One suck measure, called the spatiotemporal index (STI) represents how consistently an infant can organize their NNS skills.

Feeding diffculties in the preterm infant

Specific oral feeding deficits seen in preterm infants include the following3:

- Poor arousal

- Poor tongue positioning

- Suck-swallow-breathe discoordination

- Inadequate sucking bursts

- Tonal abnormalities

- Discoordination of the jaw and tongue during sucking

- Discomfort or lack of positive engagement

- Signs of aspiration

- Difficulty regulating breathing

- Inability to maintain an appropriate physiologic state to complete the feeding

They are also found to have higher nutritive suck frequency, with shorter suck duration, and less sucking smoothness during bottle feedings,35 as well as weaker muscle tone around the mouth, immature reflexes and less sensitivity and strength in their tongue.36-38

In order to discharge preterm infants from the hospital, they must meet several neurologic and physiologic milestones that ensure they will be able to thrive once they go home, the final one being the ability to transition off the feeding tube to independent oral feedings.1 Approximately 40% of premature infants will have difficulty transitioning from enteral to oral feeding due to oral feeding deficits.39 Prolonged use of a feeding tube is associated with an increased length of stay which can be detrimental to an infant’s short- and long-term development.40 Approximately 3% of preterm infants born 28-33 weeks gestational age and 5% of infants born <28 weeks will demonstrate feeding difficulties past full-term age equivalent, necessitating discharge to home with a feeding tube in place.41

Approximately

40%

of premature infants will have difficulty transitioning from enteral to oral feeding due to oral feeding deficits.

Approximately 3% of preterm infants born 28-33 weeks gestational age and 5% of infants born <28 weeks will demonstrate feeding difficulties past full-term age equivalent, necessitating discharge to home with a feeding tube in place.41

Long-term consequences of feeding difficulties

After NICU discharge, infants with poor oral feedings are diagnosed with a pediatric feeding disorder, defined as impaired oral intake that is not age-appropriate and is associated with medical, nutritional, feeding skill and/or psychosocial dysfunction.42 Symptoms include refusing to eat appropriate volumes or developmentally appropriate varieties of foods; symptoms of dysphagia or aspiration, such as coughing, choking, gagging or respiratory compromise; problematic feeding behaviors, such as increased stress, crying, irritability; and oral motor difficulty affecting bolus manipulation and swallowing.4 A recent meta-analysis included 22 studies and found that problematic feeding was diagnosed in 42% of prematurely born infants under 4 years old,4 and that prevalence was higher at 6-15 months than at 15 months to 2.5 years.43

In some cases, infants who were discharged home on full oral feedings may need to be placed with a feeding tube to assist with nutritional intake, increasing the prevalence of tube feedings to 7.3% for all NICU graduates.44 Prolonged nasogastric tube >2 weeks was independently associated with increased eating difficulties.45 In a retrospective cohort of 194 preterm infants with feeding difficulties referred to a specialized feeding disorders program, 40% of preterm infants with feeding difficulties were discharged on G-tube feeds, and out of these, the majority (78%) were still receiving either full or partial G-tube feeds at 1 year of age.40

Speech and language delays are closely associated with feeding problems as the neural pathways for feeding and speech are inextricably linked and these infants often present with speech-language delays. Infants with a history of feeding problems have delayed babbling and speech-language production that may begin to show up between 18 and 26 months.46

Problematic feeding was diagnosed in 42% of prematurely born infants under 4 years old,4 and that prevalence was higher at 6-15 months than at 15 months to 2.5 years.43

40% of preterm infants with feeding difficulties were discharged on G-tube feeds, and out of these, the majority (78%) were still receiving either full or partial G-tube feeds at 1 year of age.40

Improving NICU practices

Feeding problems are complex; therefore, dynamic assessments and interventions early on in a NICU stay are required. When using a whole-child approach, where the infant’s specific feeding difficulties are considered, neonatal health providers can help prevent potential long-term challenges.18

There are several bedside tools available for oral motor assessment of preterm infant NNS and oral feeding skills, although it is reported that informal clinical assessments are used more frequently in the NICU than formal assessment tools.5

This is not ideal because most of these tools rely on clinical judgment, which can result in subjective interpretations. Furthermore, these informal assessments have been noted to make the ability to consistently assess skills, measure progress and translate findings to the team difficult.47 Although there are multiple diagnostic factors required to appropriately determine an infant’s feeding skills, assessing NNS has proven to be an important factor to prioritize.

To date, there is only one tool available to objectively assess NNS in infants: the Cardinal Health™ Kangaroo NTrainer™ System. This device can measure an infant’s full oral motor activity, providing the medical team with four numerical metrics that measure the NNS:

Strength of sucking compressions

Number of sucking bursts per minute

Number of sucks per burst

STI

When analyzed together with the NTrainer™ Assessment, it defines an infant’s NNS strength, coordination, rhythmicity and stamina. Healthcare providers can use this data to help validate their clinical findings. This validation often helps team members better understand the nature of the problem and improves the appropriateness of the therapeutic plans created.

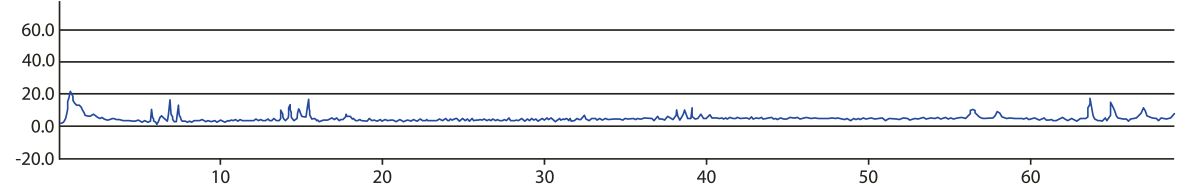

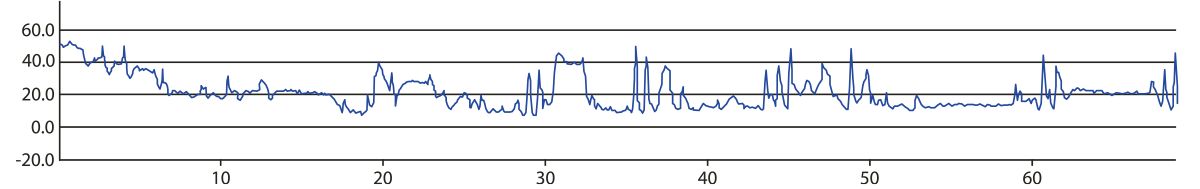

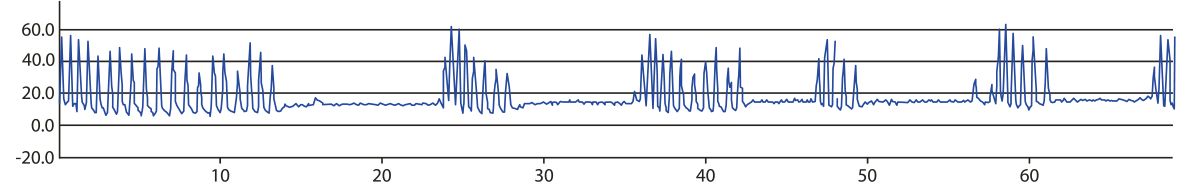

Initial NNS assessment

Weak; lacks stamina

NNS assessment after starting NTrainer™ Therapy

Strong; unorganized

Final NNS assessment after NTrainer™ Therapy

Strong; coordinated

Regarding treatment, there is no single solution for helping preterm infants achieve successful oral feedings. The literature support many interventions that are proven to help, such as cue-based feedings,48 slow-flow nipples,49 elevated side-lying positions50 and pacing the infant’s sucking bursts.51 Less directly, interventions such as massage,52 music therapy53 and milk drops54 are also found to be beneficial. To specifically improve the NNS of premature infants, the evidence supporting oral motor stimulation programs are overwhelmingly positive.

Oral motor stimulation is the use of stroking pressure applied to peri- and intra-oral structures including the cheeks, lips, jaw, tongue, palate and gums.37 The underlying hypothesis is that these maneuvers affect and train underlying neuronal and musculoskeletal structures that improve suck, swallow and respiration coordination.55 It is recommended to be provided during tube feeding, while being held or combined with kangaroo mother care (KMC) and NNS.56

Studies have shown that such programs can improve sucking abilities, feeding efficacy and motor function,37 speed the transition from tube feeding to full oral feeding, decrease length of stay57 and reduce risk of requiring a feeding tube at discharge.58 Additionally, this care practice may increase the likelihood of breastfeeding at discharge,56 which provides many other benefits for the preterm infant and their families. One caveat, however, is that oromotor stimulation programs are not always administered consistently. Up until recently, there wasn’t a systematic and structured method of implementing oral motor therapy, despite clinical evidence indicating the positive effects of consistent oral motor stimulation on feeding outcomes in neonates.59 Variability of practice in providing oral stimulation could be detrimental in providing high quality of care in the NICU; therefore, with the introduction of the NTrainer™ System 2.0, consistent therapy can now be delivered to neonates.

The NTrainer™ System is an evidence-based device that improves an infant’s NNS by providing consistent, gentle pulses through a pacifier, in a highly specialized pattern that mimics a mature NNS pattern. The NTrainer™ System therapy has several clinically proven benefits. For example, its use can improve NNS strength, rhythmicity and consistency;30,60 increase parent involvement and satisfaction;61,62 and can shorten the time it takes infants to achieve full oral feeding and increase the percent of oral feedings more successfully than just oral stimulation with a pacifier.63 Studies on preterm infants using EEG progression brain imaging have found that the type of consistent oral stimulation provided by the NTrainer™ System have a positive impact on infants’ brains in terms of modulating amplitude and range of electrocortical activity,64 and reorganization of activity in the left and right hemispheres.65